NASA Scientists Discover Potential Oceans on Uranus’ Moons, Increasing Likelihood of Habitability

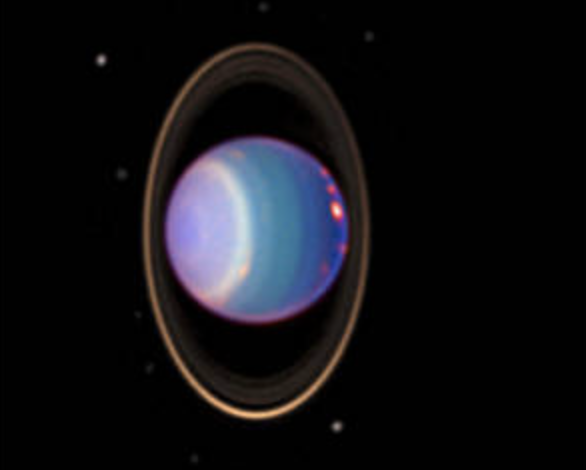

NASA scientists have concluded that four of Uranus' largest moons likely contain an ocean layer between their cores and icy crusts

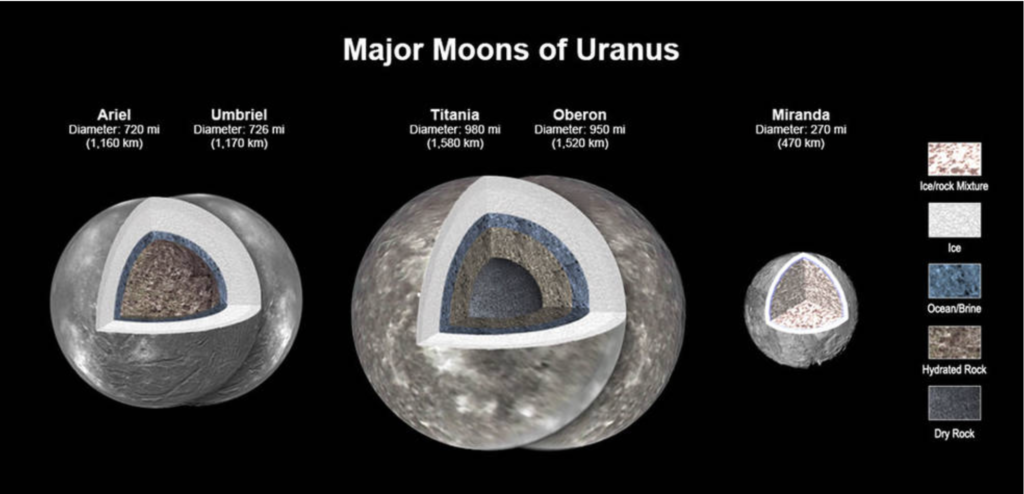

NASA scientists have concluded that four of Uranus’ largest moons likely contain an ocean layer between their cores and icy crusts, according to a re-analysis of data from NASA’s Voyager spacecraft and new computer modeling. This study is the first to detail the evolution of the interior makeup and structure of all five large moons: Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, Oberon, and Miranda. The research suggests that four of the moons have oceans that could be dozens of miles deep.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

At least 27 moons circle Uranus, with the four largest ranging from Ariel, at 720 miles (1,160 kilometers) across, to Titania, which is 980 miles (1,580 kilometers) across. The size of Titania makes it the most likely to retain internal heat caused by radioactive decay. The other moons had previously been considered too small to retain the heat necessary to keep an internal ocean from freezing, especially as heating created by the gravitational pull of Uranus is only a minor source of heat.

The study revisited findings from NASA’s Voyager 2 flybys of Uranus in the 1980s and from ground-based observations. The authors built computer models infused with additional findings from NASA’s Galileo, Cassini, Dawn, and New Horizons, each of which discovered ocean worlds, including insights into the chemistry and the geology of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Pluto and its moon Charon, and Ceres, all icy bodies around the same size as the Uranian moons.

By investigating the composition of the oceans, scientists can learn about materials that might be found on the moons’ icy surfaces as well, depending on whether substances underneath were pushed up from below by geological activity. In addition, determining that ammonia and chlorides may be present means that spectrometers, which detect compounds by their reflected light, would need to use a wavelength range that covers both kinds of compounds.

However, there are still many questions about the large moons of Uranus, and there is plenty more work to be done, said lead author Julie Castillo-Rogez of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “We need to develop new models for different assumptions on the origin of the moons in order to guide planning for future observations,” she said.

Digging into what lies beneath and on the surfaces of these moons will help scientists and engineers choose the best science instruments to survey them. Scientists can use that knowledge to design instruments that can probe the deep interior for liquid